For 57th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia 2017 Viva Arte Viva the Padiglione Italia, curated by Cecilia Alemani — director and chief curator of New York City’s High Line Art — presents the exhibition Il Mondo Magico (Italian for ‘the magic world’), which puts on display the works of three young Italian artists: Roberto Cuoghi, Adelita Husni-Bey, and Giorgio Andreotta Calò. An unusual way of using the 1,900 square meteres of the Tese delle Vergini dell’Arsenale, where the Padiglione Italia is located since 2009: if in previous editions this pavilion was haunted by a pathological horror vacui (Latin for ‘horror of emptiness’), in Biennale 2017, the magic world regards void as an added value that exalts works of art.

The exhibition, characterised by a strong evocative power, draws inspiration from the 1948 book Il mondo magico by the Neapolitan anthropologist Ernesto De Martino, a renowned researcher of the sense of ‘magic’ that is typical of popular culture rooted in Italian society imbued with beliefs, rituals, and myths. Cuoghi, Husni-Bey, and Andreotta Calò become the demiurges of novel cosmogonies that lead viewers into a sacral dimension, where magic and imagination are the means to read this ‘tale of tales’.

Roberto Cuoghi, Imitazione di Cristo, 2017

Roberto Cuoghi, fascinated by the medieval ascetic text Imitatio Christi (Latin for ‘imitation of Christ’), builds within the pavilion a workshop–installation where statues of Christ on the Cross are moulded every day using organic materials. The sacred effigies are then stored in a system of transparent igloos, a new futuristic cathedral, where the decomposition of matter takes place: moulds and bacteria corrode the body of the Christ modifying its thickness and colour. According to a ‘new technological materialism’, as it was defined by Cuoghi, the entire process investigates the phases of creation, deterioration, death, and regeneration (or resurrection): endless serial reproduction does not beget the ever-identical, instead it provides the formula for the eternally different, since every copy of the body on the cross differs from the others.

Adelita Husni-Bey, The reading / La sessione, 2017

The work by Adelita Husni-Bey centres on a dialogue about the world: on the big screen plays the video of a workshop that took place in New York City in February 2017. In it, a group of young people with diverse backgrounds, selected via an open call among the education departments of various New York museums, talk about race, gender, class, and various other contemporary topics, like technology or the intensive exploitation of the planet’s natural resources. These subjects are translated by Husni-Bey into the pictures of tarot cards that the young people see for the first time.

And it is just seeing these cards that, as a result of an occult exoteric force, triggers the debate, an activity that alternates with experimental performance exercises: an apotropaic dance to save the human race. As the screening proceeds, from the floor appear illuminated silicone arms: portions of a prosthetic body that is dependent on an ever more digitalised future.

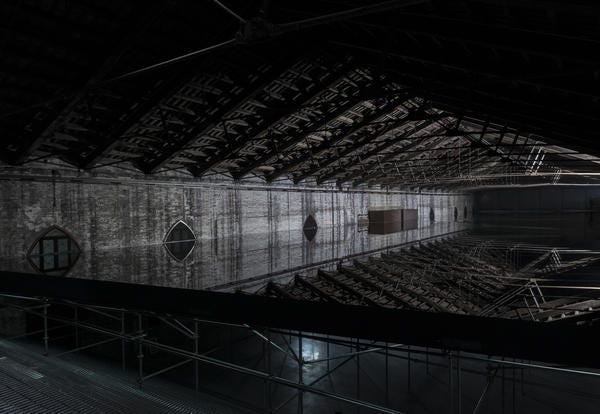

Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Senza titolo (La fine del mondo), 2017

The installation by Giorgio Andreotta Calò builds inside the Tesa delle Vergini a dizzying double world. Aiming to recreate the mystical atmosphere of the text La fine del mondo (Italian for ‘the end of the world’) by Ernesto de Martino and of the Roman myth of mundus Cereris (Latin for ‘the world of Ceres’), which told of a breach in the ground connecting the world of the living to that of the dead, Andreotta Calò relies on architecture to achieve a truly unexpected and alienating scenic effect.

The Basilica-like space is turned into a five-aisle room by a system of metal pipes linked to bronze sculptures representing large seashells; the exhibition route continues on the staircase that leads to the upper level, where the magic takes place. At the top of the stairs, the horizon opens up, and the pipes turn out to be the supporting columns of a gigantic basin of black water, where the entire beamed ceiling of the pavilion is reflected upside-down.

The simultaneous cohabitation of the split elements generates a chasm, a sinking feeling that converts into a sublime image — fascinating and menacing at the same time. Andreotta Calò places the observer before a mirage: the thick and dark water becomes the surface where the vault of heaven and that of the underworld come together. Choosing where to enter is up to you.