Antonio Sant’Elia didn’t build much himself, yet he left an indelible mark on the history of architecture. Yes, he literally left a mark, as his designs are extraordinary, visionary and inspired not only architects but also designers (such as La Corbusier and his ideal city, functional and organised) and playwrights.

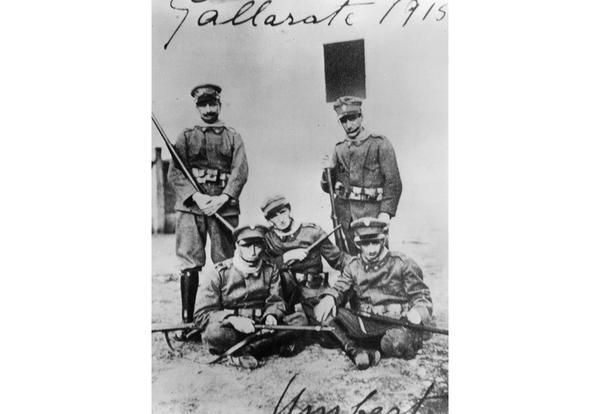

From the left: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Antonio Sant'Elia and Mario Sironi in the Italian army during WWI.

Just think of Metropolis by Fritz Lang, a cinematography masterpiece from 1927 set in a dystopian future where social classes reflect the city’s structure. Shiny skyscrapers for the rich, and dark and dusty basements for the poor. Science fiction cities, from Blade Runner to The Fifth Element, Brazil and Immortal, were all inspired by his shapes, materials and their frenetic buzz.

Born in 1888 in Como, Antonio Sant’Elia became a master builder in 1905 and started contributing to the completing works to the Canale Villoresi. While working in Milan, he was exposed to issues related to the city’s sudden expansion and to technological and hygienic innovations promoted by the council.

Perhaps, his speculation on futuristic cities started exactly here. He attended courses at Accademia di Brera and graduated in architecture in Bologna in 1912.

Antonio Sant’Elia’s only two creations are Villa Elisi in San Maurizio (near Como) and a monument to the fallen in Como based on one of his designs from 1914 and built by G. and A. Terragni (1931-1933).

Designed in 1912 together with his friend and sculptor Girolamo Fontana, Villa Elisi was just a farm building with a Klimt-inspired frescoed tympanum with a clear influence from the Viennese Secession. Sant’Elia always mentioned Otto Wagner as his main teacher and source of inspiration, however, from 1913 onwards, he left that movement behind and started developing his visions about the city of the future.

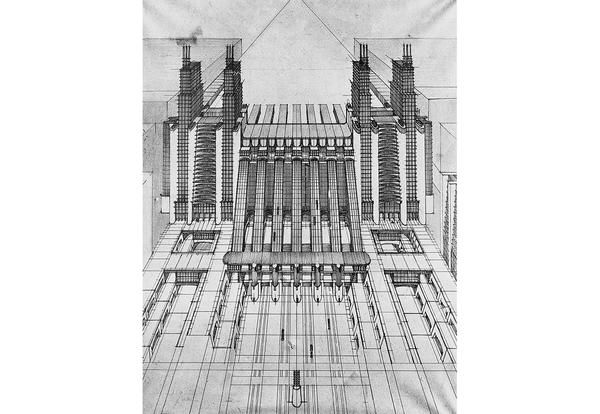

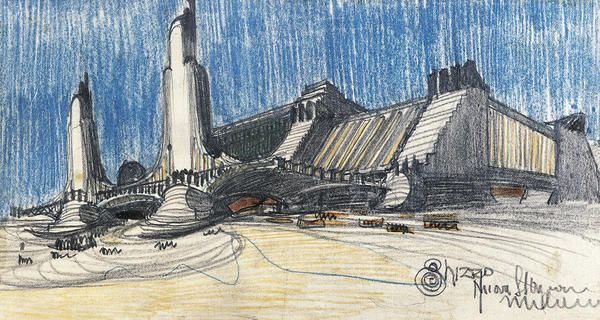

A futuristic train station and airport, 1913. Photo: Getty Images

A remarkable amount of drawings from 1913 and 1914 features villas, towers, bridges, lighthouses, laboratories and stations that together start shaping his idea of futuristic city and later of futuristic architecture.

In the Futuristic Architecture Manifesto of 1914, he expressed his utopias but also his concrete ideas to change the way buildings were conceived. For instance, the idea of locating elevators on the outside of buildings (away from stairs) is attributed to him. “Elevators shouldn’t be compressed like warms by sets of stairs. Stairs are now useless and elevators need to climb up façades like iron and glass snakes.

“Houses should be made of concrete, glass and iron, without paintings or sculptures, but rich in lines and mechanic simplicity. They should be as tall and wide as possible, ignoring the limits sets by municipal laws. Roads will no longer be linear but will develop on various levels, connected by metallic runways and treadmills.”

Project for Milan’s central station, 1914. Photo: DEA PICTURE LIBRARY/De Agostini/Getty Images

Unfortunately, he died too soon to see his projects come to life and he was not too lucky with design either. His tableware collection designed for silversmith Arrigo Finzi from 1914 to 1916 had a little success in 1933 with the launch of the “Sant’Elia” brand.

Cutlery, vases and silver coffee cups in retro style - quite different from Sant’Elia’s liberty style - were highly appreciated by buyers, especially by Gio Ponti.

A hammered silver centrepiece with plated metal coppery flowers by Sant’Elia.

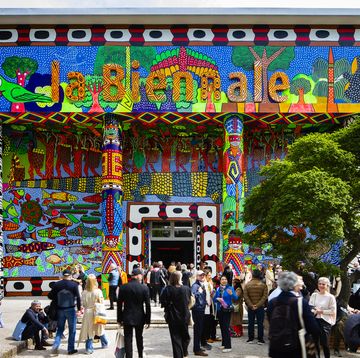

One of the last exhibitions celebrating him was at Milan’s Triennale in 2016, on the occasion of 100 years since his death. It focused on the issues of his time but mainly on his sudden and international success, aided by his sketches of contemporary skylines with glass and steel skyscrapers, of floating and suspended cities.

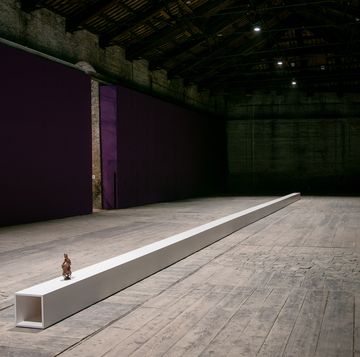

‘Antonio Sant’Elia - Il Futuro delle Città’, ended with “Il Piccolo Sant’Elia”, an installation by Alessandro Mendini, a tribute to the Italian master and to the eternal futurism present in each one of us.

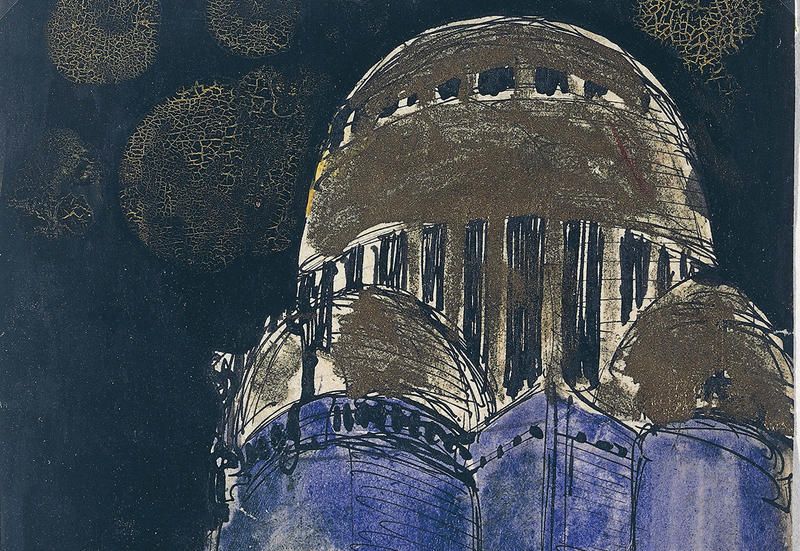

At the opening: EDIFICIO MONUMENTALE CON CUPOLA, 1911-12