Forty years after his death in Sendai, Japan, Carlo Scarpa continues to provoke a dialogue with his one of a kind, nonconformist pieces that raised the bar for Italian craftsmanship. With brilliant and refined details and a keen sense for materials, he led a new group of intellectuals to artistic greatness.

A trained architect, Carlo Scarpa would guide the generations after him through a long academic career at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia (IUAV), and through his influence, under a whole new Italian movement. He had the capacity to fuse the culture of craftsmanship with an intellectual character that truly set him apart. Creating a kind of signature, he showed ornament as a personal and unique architectural language that could be transformed into an Italian brand.

Behind some of Scarpa’s most famous works were the innovative post-war figures of Italian industry, like Adriano Olivetti, Paolo Venini, and the Brion family (owners of Brionvega). In 1969, the latter would commission Carlo Scarpa to complete the Tomba Brion, the famous reinforced concrete temple with sharp geometric paths winding through the artificial landscape. It was this very family tomb that would showcase Scarpa’s professional maturity, uniting his research on ‘deconstructing the box’ and the poetry of the materials.

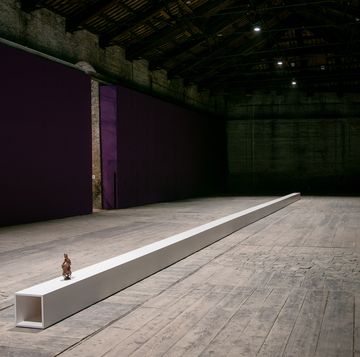

His personal approach to architecture, however, was what set him apart, especially in the restoration of monuments. His works revolutionized the way we see modern architecture, harmonizing contemporary elements with pieces from the past like he did in the famous restoration of the Castelvecchio in Verona. The spaces of the museum follow a single path, interrupted only briefly by an excursion outdoors. The curation, stripped to the essentials, emphasizes the single works, while visually connecting them along an architectural promenade that reaches its peak at the 14th century equestrian statue of Cangrande I della Scala, fixed on a modern metal cantilever.

An architect and designer, Carlo Scarpa began his career in 1932 with a fruitful collaboration as the artistic director of the famous Venini glassworks of Murano. For Venini, he designed objects that are still in production today, representing the image of the Italian brand. His glass vases and reinterpretations of the chandelier are still distinguished for their modern design and technical craftsmanship.

It was during this period that Carlo Scarpa developed his interest for the applied arts, the organic architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, oriental art, and architects of the Vienna Secession like Hoffmann, Loos, and Wagner. The clear influence of oriental architecture on Scarpa is the subject of the exhibit “Carlo Scarpa and Japan”, promoted by the Fondazione MAXXI and now visitable at the Centro Carlo Scarpa in Treviso.

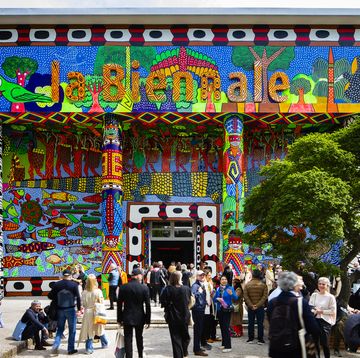

Over the same time, Carlo Scarpa entered into a group of intellectuals and artists orbiting around the Venice Biennale, for which he would curate innovative new exhibits. His work there would revolutionize museology of the 20th century, transforming museums into outposts of the avant-garde. Among the most memorable exhibits are those of Paul Klee at the Biennale in 1948, the monographic shows of Piet Mondrian and Marcel Duchamp, as well as the collaborations with Lucio Fontana and Arturo Martini.

From these innovative experiments, he gained the experience to intervene at the Canova Museum in Possagno, Treviso, where he gave life to a raw and easy styling with the art at the core of it all. Thanks to his unique, artisan approach, Carlo Scarpa often found the solutions to his problems right on the job with the other workers through tech-savvy methods, innovative aesthetics, and limited resources.

This led to his winning the Olivetti Prize in 1956, which in turn would lead to a commission for the showroom of Venice’s Piazza San Marco in 1958. Created for Olivetti, the showroom is a true masterpiece of Italian architecture, a ‘calling card’, according to Adriano Olivetti himself. It was an exhibition space that embodied the quality Olivetti had been searching for.

With an iconic suspended staircase, the small shop in the Procuratie Vecchie of Venice also featured Scarpa’s special touch: a hyper-modern space, light and transparent, and yet in complete harmony with its historical surroundings.

Each of Carlo Scarpa’s works convey a sense of learning on the job, with the capacity to read the context, the landscape, the space, or the single piece of art to be seen in a new light through the critical language of architecture.